It’s not easy to recognize learning disabilities in our kids. To the untrained eye, disorders like ADD or ADHD might look like laziness or lack of self-control—traits that many of us were (wrongly) brought up to believe are problems of character rather than problems of neurology. And we worry, that by labeling a problem we’re also labeling our kids, defining them by their challenges, rather than their gifts.

But naming a problem makes it smaller, and can help a child disentangle her identity from her learning disability. Her self-talk can shift from blaming statements like, “I can’t focus” to “my learning disability makes it hard to focus.”

In a previous post, we looked at the ways stress impairs kids’ development of executive functions—mental processes like working memory, attention, and impulse control that regulate learning and behavior. But what can we do when a child is genetically predisposed to have impaired executive functions, as in ADD/ADHD?

In honor of ADHD awareness month, we spoke with ADHD Life Tools founder Judy Bandy (RN, MA) to find out how parents can help kids with ADHD thrive.

“The most important thing is to come to it with compassion and understanding. Try to really understand what’s going on with the executive function. The biggest misconception is that they don’t care.” For example, instead of thinking that your child chose to not complete an assignment, try listing executive function issues that might be to blame.

Examples of these issues include: getting distracted, running out of time, losing important materials, forgetting to hand in the assignment, or not having the internal motivation to begin. All of these issues stem from ADHD’s effect on a child’s brain structure and neurotransmitter levels.

By playing Executive Function Detective, parents and kids can figure out exactly how their ADHD is getting in the way of their goals. One of the best ways to support a child with ADHD is to externalize underactive executive functions through tools like lists, schedules, reminders, and timers. External rewards, like treats for completing particular tasks, can also compensate for the impaired internal reward system that comes with ADHD.

Judy stresses the importance of not asking your child to try harder. Kids with ADHD are already having to try much harder than their peers in the course of a school day. They need to keep up with rapid information flow, demands on their memory, and frequent subject changes, as well as navigate social situations that require attention and impulse control. They’re exhausted at the end of the school day.

“That’s why homework time is so hard for them, because they’ve worked all day to transition and pivot.” To help prepare for homework Judy, drawing on the recommendations of Dr. Russell Barkley, suggests that kids with ADHD have an after-school snack or glucose-rich drink like Gatorade to replenish their energy, followed by an executive-function-boosting exercise routine. Once your child is ready to tackle her assignments, help her break up tasks into a schedule and practice estimating how long it will take her to complete each task.

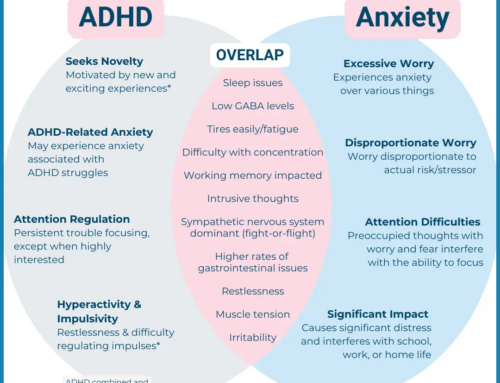

One of the trickier features of ADHD is that symptoms can be inconsistent. Kids with ADHD can focus intensely on things they’re passionate about, but are unable to focus on things that don’t interest them, no matter how much they might want to.

In other words, ADD/ADHD does not mean a child is unable to focus, rather that she has trouble regulating her focus. Research shows that people of all ages with ADHD can significantly improve their attention and impulse control with mindfulness meditation practice—so parents who may also struggle with the disorder can strengthen their own executive function skills alongside their kids.

Regardless of how your family adapts to your child’s ADHD, it’s important that you talk to her teachers, and, depending on her age, help her practice advocating for herself at school. Beyond ensuring that your child gets the accommodations she needs, teachers can keep you informed of her classroom performance, as well as any social difficulties she may be experiencing.

“It’s important to understand that progress is an uneven path,” says Judy. “You can have a system in place that works great for three days, and then it doesn’t. You’ll most likely see progress in weeks to months, but not necessarily day-to-day. So try your best to pause and step back before you react.

It’s important that kids and parents know that when they’re working on executive function they’re working on a set of skills—not character—so that when families encounter problems they can say ‘We’re not there—yet’.”

For Twin Cities-area families interested in mindfulness practice, check out Creating Harmony in the Home: Develop Self-Regulation using Yoga Calm Practice on October 26, 2017

Want to learn more about executive functions? Register for the November 16 conference From School and Home Again: Executive Function Skills Across the Day

For more ADHD resources from Judy on our Facebook page